HWS News

22 April 2025 • Research More Than Adornment: The Magical World of Renaissance Gemstones

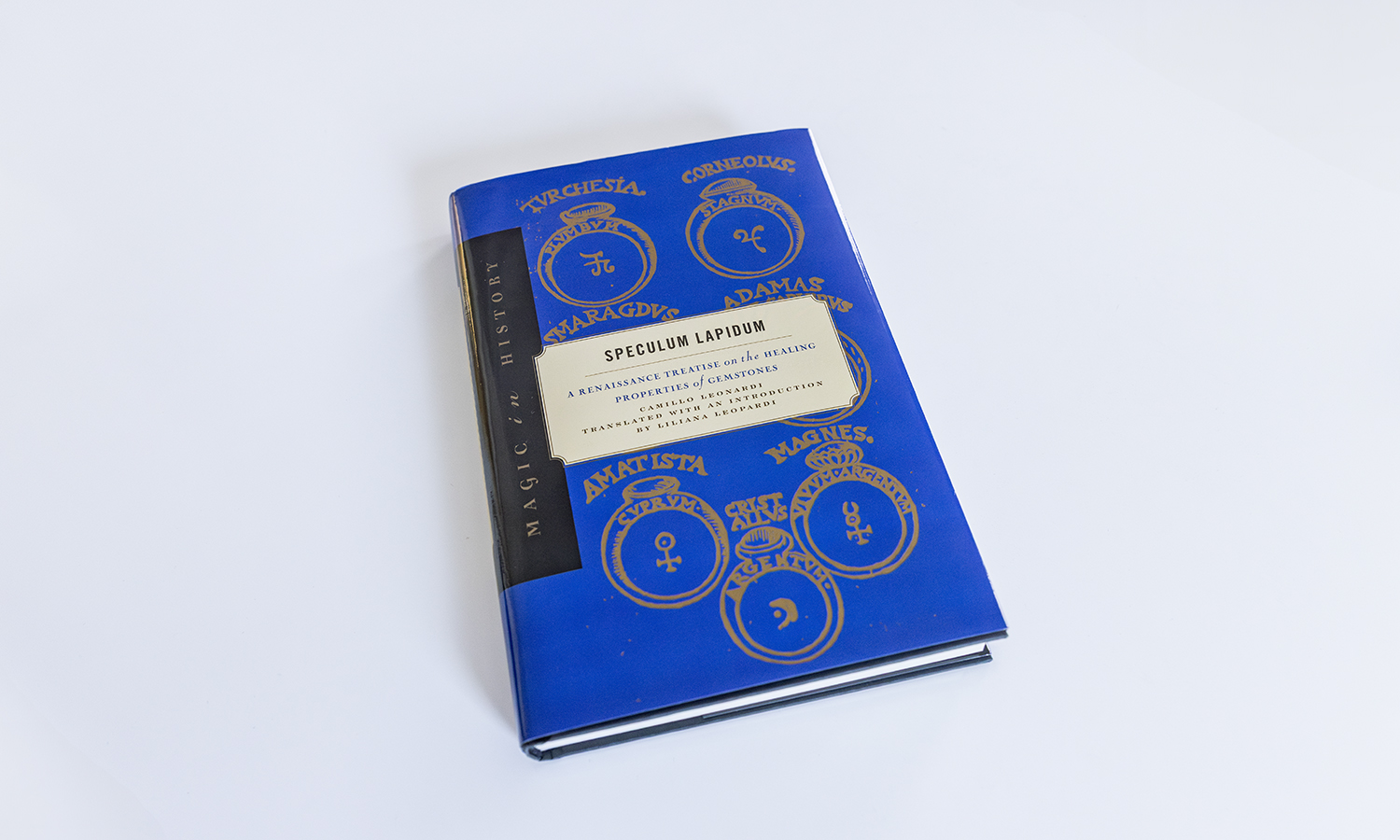

In her translation of a 1502 treatise, Associate Professor of Art and Architecture Liliana Leopardi explores how gemstones were once viewed as tools of healing, magic and political power.

Hundreds of pearls adorn Queen Elizabeth I in the symbolic “Armada Portrait,” following the failed Spanish invasion in 1588. In the portrait, great ropes of pearls drape the queen, pebble-size pearls cover the cuffs of her gown; dozens of pearls dot her ornate sleeves, and more than 20 pearls, reportedly the size of “nutmegs,” sprout from her hair. And one teardrop pearl hangs strategically from her girdle.

“She was saying, ‘Not only am I the Virgin Queen: These pearls ensure I remain the Virgin Queen,’” says Leopardi, who worked on the translation for more than a decade. In Medieval and Renaissance Europe, physicians, artists, aristocrats and royals believed precious and semi-precious stones possessed magical powers, not only when they were worn but when stones were viewed through artistic depictions as well.

“They would also grind them into potions and drink them,” Leopardi says. “We know the Medici family and the popes were treated with these kinds of potions. Paintings too, for example emeralds, would have been believed to reflect the energy of the stone on the viewer.”

Speculum Lapidum: A Renaissance Treatise on the Healing Properties of Gemstones, originally published in 1502 Venice, is organized as an encyclopedic summary of medical astrology and the astral magic of stones. The book, originally written by Physician Camillo Leonardi, was recognized as a tome of science; translated into English 500 years later by Leopardi, the 240-page book's content may now be considered akin to self-help or new age by today’s standards.

In her classes on campus where Leopardi discusses representations of men and women in Renaissance portraiture, she lectures on royalty’s use of magic and artists’ depictions of certain stones. “There is clear evidence that when it comes to these natural, magical inferences, all the royal courts of Europe had astrologers and magicians at their service in order to identify how to cure themselves, or what day to be crowned, or what day to enter the battlefields,” she says.

Stones with vivid red colors, such as red coral, were believed to be able to stop blood loss. Even the colors of certain stones possessed special energy, Leopardi explains. Amber stones, for instance, represented the sun. To harness that energy, people might wear yellow, in addition to the stone, or they might eat a lot of honey, Leopardi says. “It’s not just the gems that could capture these astrological influences. It was a whole system.”

The image on top features: The Armada portrait of Queen Elizabeth I is considered one of the most famous images in British history. It was painted circa 1590, two years after England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada—the most famous conflict in Elizabeth I’s 45-year reign.