HWS News

10 December 2025 • Faculty Forest Justice

Exploring moral choice in humanity’s darkest hours.

In 1942, hundreds of Jews managed to escape the ghettos of then eastern Poland (now Belarus) into thick forests, where the terrain made it impossible for German tanks to enter.

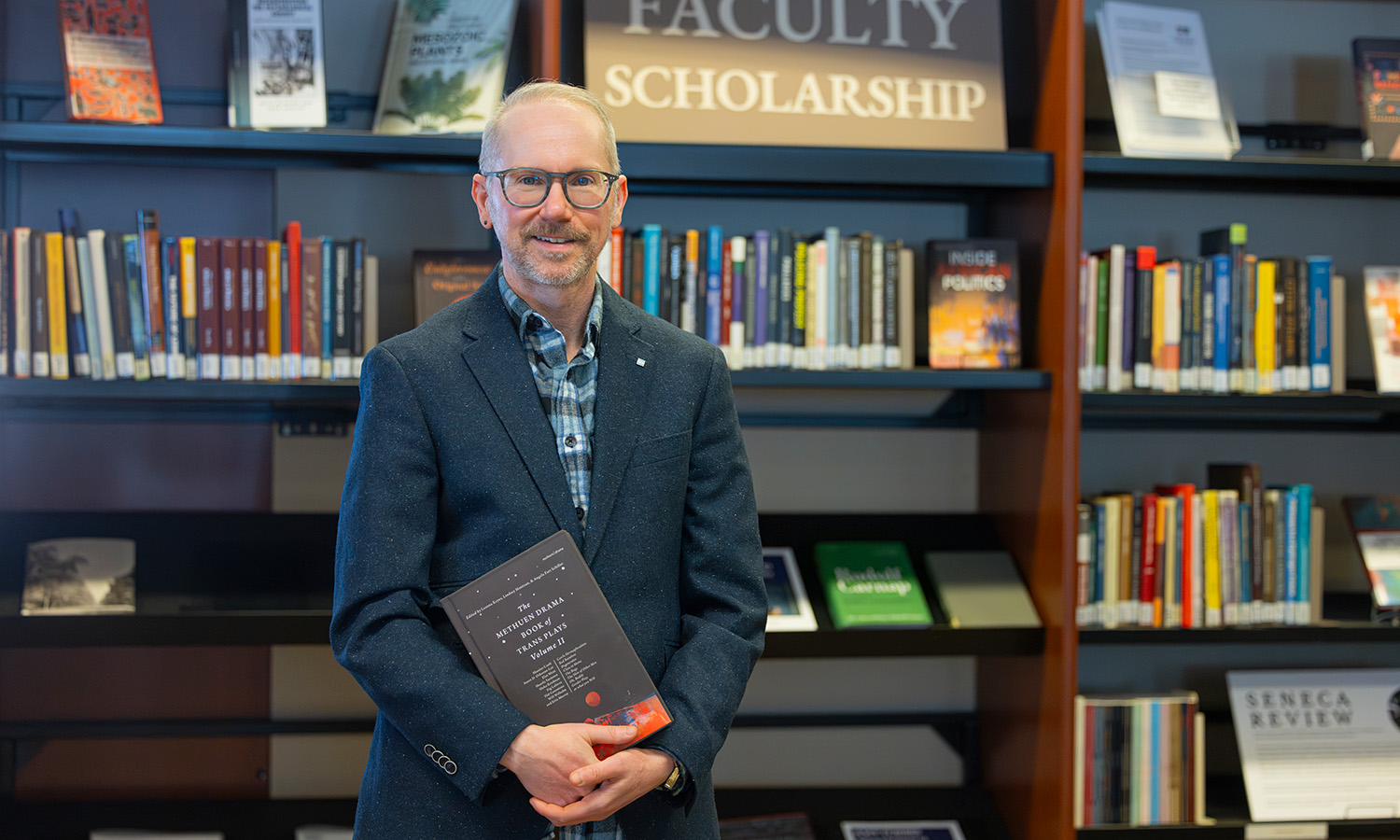

By 1943, more than 1,000 Jews were living in the forest and some were fighting back with a set of ethics born out of the genocide they were all trying to survive. Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies Michael Dobkowski took a deep dive into this understudied chapter of the Holocaust for his book Military Ethics Education and the Holocaust: Opportunities, Challenges and Moral Imperatives, published in November.

While many Jews just tried to survive in unforgiving conditions and without weapons, others formed guerrilla fighting units that became part of an underground resistance army bent on attacking Axis forces wherever they could. Jewish partisans living in the forests made it known the public was also subject to punishment for turning Jews in. Dobkowski calls it “forest justice.”

All faced impossible conditions. “They recognized earlier than most that this was a genocidal war,” Dobkowski says. “Their first obligation was survival — because if you understand the goal is the destruction of your entire people, the ethical question becomes: ‘What must you do not to be destroyed?’”

One of the many lessons about this extreme environment for readers, he says, is that not taking a stand is actually taking a stand — but without the courage to admit it.

Dobkowski’s book was co-written and co-edited with George R. Wilkes, a research fellow at the Centre for Military Ethics, King's College, London, U.K. The two scholars spent more than a decade meeting with experts from around the world to examine whether ethics emerged in these conditions, under these constant threats and how military education has or hasn’t used the Holocaust to train future soldiers.

Wilkes and Dobkowski used case studies to explore how people under extreme pressure risk their lives to do the right thing — or not. The book includes, for example, an essay on the rescue of Danish Jews by the Danish people and an essay on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Protestant theologian who entered a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

Military Ethics Education and the Holocaust was born out of years of interdisciplinary collaboration, Dobkowski says. For more than two decades, he has met every other summer with an international group of scholars, artists, educators and activists at Wroxton College in England. The seminar — originally known as the Goldener Seminar on the Holocaust — was built on dialogue rather than formal academic papers, he says, and served as a space for conversations across cultures, disciplines and religious traditions.

It was in this setting that Dobkowski met Wilkes, a historian of contemporary Europe whose work increasingly moved toward military ethics and peace studies. Their ongoing conversations led them to look at how the history of the Holocaust informs military education in countries including the United States, Austria, Lithuania, Australia and Israel.

At its core, the volume asks a deceptively simple question: Has the Holocaust influenced the ethical frameworks used to train future military leaders? And if so, where in the curricula is it found and how effective is it deemed?

While the second half of the book uses case studies, the first half features experts who examine Holocaust education within elite military academies around the world. Dobkowski points to seminars at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum designed for midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy, cadets at West Point and officers at the Marine Corps War College.

Drawing from survivor interviews and memoirs, Dobkowski’s essay in the book’s second half explored how “forest justice” was developed to protect communities and restrain indiscriminate violence. These were not formal militaries, he notes, yet they were deeply intentional about their choices.

Dobkowski’s research was difficult at times but ultimately served to reorient his understanding of hardship. After spending years immersed in the lives of partisans who survived for months or years in the woods with little food, no shelter and the constant threat of death, Dobkowski says their resilience inspired him. “We live with so many artificial values. These were ordinary people who became extraordinary, and they did it without ego or self-promotion. Hearing their stories grounds you.”

From the experience, Dobkowski says he is branching out into fiction writing for the first time in his long writing career, using what he learned about the partisans’ experiences.

“I’m not a fiction writer, and I don’t pretend to be a fiction writer, but I want to see if I can tell these stories in a different way.” The characters and dialogue will be fictional, he explains, but the situations are historical. “I’m not making up history.”

As for Military Ethics Education and the Holocaust, Dobkowski says he hopes the work encourages readers — in and outside the military — to reflect on moral agency, responsibility and the consequences of action and inaction. “All of us face choices,” he says. “Sometimes we hope we’ll never face the extreme choices others confronted, but the responsibility to think ethically about our decisions is always with us.”

Top: Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies Michael Dobkowski is a scholar of the American Jewish experience, Holocaust studies, religion and violence, Jewish thought and antisemitism.